HAMBANTOTA, Sri Lanka -- The risks of doing business with Beijing are laid out plainly in Sri Lanka, which is undergoing a major political and economic crisis due in part to Chinese loans and infrastructure projects gone awry, analysts warn.

The lessons learned in Sri Lanka provide a cautionary tale for borrowers of Chinese loans and recipients of Chinese infrastructure projects -- particularly those associated with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also known as One Belt, One Road (OBOR), they say.

China's debt trap blueprint is straightforward, Maj. (ret.) Amit Bansal, a defence strategist and international affairs analyst, said at an online conference last Friday (July 15) hosted by Red Lantern Analytica (RLA), an independent think-tank based in India.

"The country must be strategically located, it must be poor and should have corrupt politicians in administration. Once the 3 conditions are met; China offers generous loans & gradually takes its sovereignty," RLA tweeted, quoting Bansal.

![The Lotus Tower, a floral-shaped skyscraper bankrolled by Chinese funds, is pictured in Colombo, Sri Lanka, on May 5. The tower's colourful glass facade dominates the capital's skyline, but its interior has never been opened to the public. [Ishara S. Kodikara/AFP]](/cnmi_pf/images/2022/07/22/36319-000_329h4et-585_329.jpg)

The Lotus Tower, a floral-shaped skyscraper bankrolled by Chinese funds, is pictured in Colombo, Sri Lanka, on May 5. The tower's colourful glass facade dominates the capital's skyline, but its interior has never been opened to the public. [Ishara S. Kodikara/AFP]

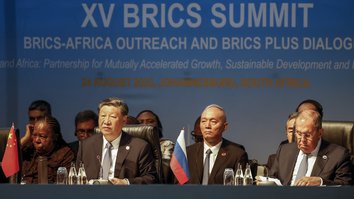

![Chinese President Xi Jinping (centre) signs a visitor's book as then-Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa (right) looks on during a welcome ceremony at the Bandaranaike International Airport in Katunayake on September 16, 2014. [Lakruwan Wanniarachchi/AFP]](/cnmi_pf/images/2022/07/22/36320-000_del6353331-585_329.jpg)

Chinese President Xi Jinping (centre) signs a visitor's book as then-Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa (right) looks on during a welcome ceremony at the Bandaranaike International Airport in Katunayake on September 16, 2014. [Lakruwan Wanniarachchi/AFP]

China's pattern of offering loans to countries in the name of BRI is the same, said J. Jeganaathan, an assistant professor of national security studies at Central University of Jammu.

"They have always chosen authoritarian regimes lacking accountability and public transparency," he said, according to RLA. "They offer loans and wait for the debt to trap the country."

Many countries in the Middle East and Central Asia, including Iraq, Egypt, Iran, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, all of whom owe billions to China, fit this pattern.

String of pearls

In Sri Lanka, examples of white elephant projects that helped fuel the crisis abound: the world's "emptiest" airport, a revolving restaurant without diners, the 350-metre-high Colombo Lotus Tower, a massive cricket stadium, the hardly used International Conference Hall, dozens of unused roads and bridges, and a debt-laden seaport, among others.

Despite assurances from Sri Lankan and Chinese officials that Beijing's investments in the country are "purely economic", observers see ulterior motives.

"Indeed, Sri Lanka is the 'crown jewel' of China's multibillion dollar BRI across the Indo-Pacific region, which connects the Hambantota Port, the Colombo Port City, the Colombo Lotus Tower and many other overwhelming infrastructure projects," said Patrick Mendis, a former American diplomat and a military professor in the NATO and Indo-Pacific Commands of the US Department of Defence.

"These ports could easily be converted into dual-purpose military and civilian use compounds," he wrote July 11 in the Harvard International Review.

"Moreover, the nearby Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport was built with the possible intention of a dual civil-and-military installation for future use."

China opened its first overseas military base in 2017 in Djibouti, reportedly to facilitate maritime operations around the Indian Ocean and East Africa. Beijing used the threat of piracy in the Gulf of Aden and its desire to secure critical international sea lanes as justification.

Authorities in Beijing have used that same line of reasoning to make the case for a military base in western Africa as well.

When news broke late last year that China was secretly building a military base in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), alarm bells rang throughout the region and beyond.

In recent years, in addition to the massive infrastructure drive in Sri Lanka, China has built commercial port facilities in Pakistan, Iran and other key areas that could be used by its rapidly expanding navy.

These are all part of Beijing's "string of pearls" strategy to link mainland China to the Horn of Africa via a network of military and commercial facilities.

In mid-January, Tehran announced it was beginning the implementation of a 25-year Comprehensive Strategic Co-operation Agreement with China, signed last year.

Under the terms of the agreement, Iran would be involved in the BRI through the launch of investment projects worth $400 billion.

Though the deal is ostensibly commercial in nature, Chinese investment in the Iranian ports of Jask and Chabahar would allow its rapidly growing navy to expand its reach.

In another example, China entered into a secret agreement with Cambodia to allow its navy to use a base in that country, the WSJ reported in 2019, citing US and allied officials.

Both Chinese and Cambodian officials denied the reports, calling them "fake news" and "rumours".

But now China is secretly building a naval facility in Cambodia for the exclusive use of its military, the Washington Post reported June 6, citing Western officials.

"All these projects were initially promoted within the BRI as development assistance," according to Mendis. "In fact, the BRI has been the ambitious foreign policy strategy of China to bring developing countries under its realm of influence as shown in the 'cautionary tale' of Sri Lanka."

Crisis in Sri Lanka

After months of blackouts and acute shortages of food and fuel in Sri Lanka, weeks of largely peaceful protests demanding the government resign over its economic mismanagement turned violent in May, leaving five people dead and at least 225 wounded.

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa fled the country in July.

The crisis has been exacerbated by Chinese-funded projects that stand as neglected monuments to government extravagance.

The centrepiece of the infrastructure drive was a deep seaport on the world's busiest east-west shipping lane that was meant to spur industrial activity.

Instead, it has haemorrhaged money from the moment it began operations.

"We were very hopeful when the projects were announced, and this area did get better," Dinuka, a long-time resident of Hambantota, told AFP.

"But now it means nothing. That port is not ours, and we are struggling to live."

The Hambantota port was unable to service the $1.4 billion in Chinese loans rung up to finance its construction, losing $300 million in six years.

In 2017, a Chinese state-owned company was handed a 99-year lease for the seaport -- a deal that sparked concerns across the region that Beijing had secured a strategic toehold in the Indian Ocean.

Overlooking the port is another Chinese-backed extravagance: a $15.5 million conference centre that has been largely unused since it opened.

Nearby is the Rajapaksa Airport, built with a $200 million loan from China, which is so sparingly used that at one point it was unable to cover its electricity bill.

In the capital, Colombo, there is the Chinese-funded Port City project -- an artificial 665-acre island set up with the aim of becoming a financial hub rivalling Dubai.

But critics have already sounded off on the project becoming a "hidden debt trap".

Mired in debt

China is Colombo's biggest bilateral lender and owns at least 10% of its $51 billion external debt.

The true number is substantially higher if loans to state-owned firms and Sri Lanka's central bank are taken into account, say analysts.

Unable to service its growing debt burden, and with credit rating downgrades drying up sources of fresh loans on the international money market, Sri Lanka's government in April announced a default on its foreign loan obligations.

It had sought to renegotiate its repayment schedule with China, but Beijing instead offered more loans to repay existing borrowings.

That proposal was scuttled by Sri Lanka's appeal for help to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

"China has done its best to help Sri Lanka not to default, but sadly they went to the IMF and decided to default," Chinese Ambassador Qi Zhenhong told reporters at the time.

For many Sri Lankans, the largely unused infrastructure projects have become potent symbols of the risks of doing business with China.

"We are neck-deep in loans already," said Krishantha Kulatunga, owner of a small stationery store in Colombo.

Kulatunga's business sits near the entrance to the Lotus Tower, a floral-shaped skyscraper bankrolled by Chinese funds.

The tower's colourful glass facade dominates the capital's skyline, but its interior -- and a planned revolving restaurant with panoramic views of the city -- has never been opened to the public.

"What is the point of being proud of this tower if we are left begging for food?" asked Kulatunga.

![Thousands of anti-government protesters stormed into Sri Lankan Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe's office on July 13, hours after he was named as acting president. [AFP]](/cnmi_pf/images/2022/07/22/36318-000_32eb9wz-585_329.jpg)