Countries allied closely with China -- or those heavily indebted to it -- are facing the reality that they are increasingly at risk of being dragged into Beijing's geopolitical games and even potential future conflicts, analysts say.

These concerns are becoming more heightened as Beijing's sabre-rattling and its territorial disputes with its neighbours threaten global peace and risk choking the world's busiest shipping lanes with global economic repercussions.

Many say there appears to be a growing pattern of leverage Beijing is bringing to bear in its geopolitical decisions.

"China is employing its growing economic power as a means of coercing or enticing other states to comply with its foreign policy priorities or principles of international relations," said a recent study by the Atlantic Council titled "Co-operation with China: Challenges and opportunities".

![Pakistani military personnel during a patrol in 2018. Pakistan is seen as particularly vulnerable to suffering the consequences of being closely allied with China. [Pakistan Army]](/cnmi_pf/images/2022/09/21/37211-pakmil-585_329.jpg)

Pakistani military personnel during a patrol in 2018. Pakistan is seen as particularly vulnerable to suffering the consequences of being closely allied with China. [Pakistan Army]

![Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and Fijian Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama attend a joint news conference in Fiji's capital, Suva, on May 30. During the conference, the leaders of 10 Pacific island nations rebuffed China's push to bring them into Beijing's orbit. [Leon Lord/AFP]](/cnmi_pf/images/2022/09/21/37212-000_32bj8jg-585_329.jpg)

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and Fijian Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama attend a joint news conference in Fiji's capital, Suva, on May 30. During the conference, the leaders of 10 Pacific island nations rebuffed China's push to bring them into Beijing's orbit. [Leon Lord/AFP]

Beijing is using this power to "organise the support of other illiberal governments at the United Nations to forward its interests, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and promote its ideas on human rights and state sovereignty to contest core principles of political freedoms on the world stage", it continued.

Under Beijing's thumb

The BRI, also known as One Belt, One Road (OBOR), is Beijing's massive infrastructure project linking 78 countries across Asia, Africa, Europe and Oceania.

Development of sea port and land transportation facilities under the BRI is promoted as commercial in nature, but critics say they serve a dual purpose -- allowing for China's rapidly growing military to expand its reach.

The infrastructure drive aims to connect China to the Horn of Africa via a network of military and commercial facilities.

As part of its "String of Pearls" strategy, China's sea lanes run through several major ports from the Maldives to Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Iran and Somalia, and through several key maritime choke points.

The BRI continues inland from these important seaports, reaching other parts of the Middle East, Central Asia and Africa.

The String of Pearls also gives Beijing an advantage and a pressure lever should a full-scale conflict erupt over Taiwan.

China's military drills last month encroaching on Taiwan are the most recent reminder of the threat that Beijing's military expansionism poses.

The drills bode ill for other key waterways in which China either has active disputes or where it is expanding its military presence.

Beijing claims sovereignty or some form of exclusive jurisdiction over most of the South China Sea, and is giving Chinese names to places across Asia as a way to build a legal case for those claims.

China's claim over the South China Sea -- through which trillions of dollars in trade passes annually -- competes with claims from Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam.

In Central Asia, Beijing has also been floating the idea of the return of "its" territories in state media to gauge the reaction of the local population in what observers say is a direct threat to the region's sovereignty.

Economic coercion

Even outside the BRI scheme, China has used "economic coercion" and "bullying" in an attempt to push policies favourable to Beijing.

"Beijing has used the threat and imposition of trade-restrictive measures to punish over a dozen countries for pursuing policies deemed harmful to Chinese interests," Bonnie S. Glaser, director of the China Power Project at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, DC, wrote in January 2021.

She provides a long list of examples over the past dozen years, including Norway, Japan, the Philippines, Mongolia, South Korea, Canada, New Zealand, Sweden, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, Australia and the city of Prague.

Beijing's "bullying" has had mixed results, she said, but China continues to see the benefit of using coercion.

"In the absence of collective pushback, China will continue to use non-transparent trade restrictions to punish countries that damage Chinese interests, to compel those countries to modify or reverse policies that Beijing considers harmful, and to deter others from being emboldened to similarly challenge China," she concluded.

These tactics follow a pattern, analysts say.

"Chinese leaders make a determination that the statements or policies of a certain country undermine some aspect of the party's rule or security interests," Asia Society Policy Institute vice president Wendy Cutler and McLarty Associates senior adviser James Green wrote in November 2020 in The Straits Times.

"The Chinese trade bureaucracy then looks for ways to 'punish' the offending country by imposing opaque trade or investment restrictions without official notifications."

'Ally' Pakistan: a case study

Close ally Pakistan provides an example for prudence.

Twice in recent months, its friendship with China has proven to undermine its national interests.

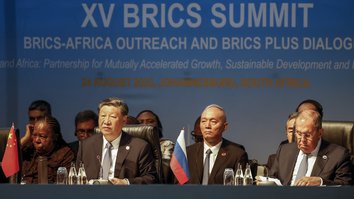

In June, Pakistan was sidelined from a high-level dialogue on global development at the 14th summit of BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) nations.

China, the host nation, had engaged with Pakistan before the BRICS meetings, where decisions are made on extending invitations to non-members.

But when it came time to support Islamabad's participation in a key global event, Beijing turned its back on its supposed ally.

"Regrettably one member blocked Pakistan's participation," Pakistan's Foreign Office said.

When asked about the decision, China deflected blame.

"China and Pakistan are all-weather strategic co-operative partners," said Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijiang.

That incident follows a self-damaging decision Pakistan made last December to skip the US-led Summit for Democracy, in part due to its close relationship with China, which was not invited.

In response, Zhao tweeted that Pakistan was a "real iron brother" for declining to attend the summit.

By putting China's interests ahead of its own national interests, Pakistan lost out in both cases.

Pushback against Beijing

There have been several recent examples of pushback against Beijing's bullying, however, indicating that nations historically indebted to China -- even smaller, politically less potent nations -- are tiring of the increasingly risky relationship.

"Overall ... China's use of economic coercion has not furthered its long-term strategic interests but instead has often had the opposite effect," a May CSIS report said.

"Over the last decade, Beijing's bullying behaviour has not only contributed to a precipitous decline in its favourability rating around the world, but it has also often failed to achieve its intended policy objectives," it said.

In late May, for example, the leaders of 10 Pacific island nations rebuffed China's push to bring them into Beijing's orbit during talks in the Fijian capital Suva with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi.

China offered to radically ramp up its activities in the South Pacific, directly challenging the influence of the United States and its allies in the strategically vital region.

The proposed pact would see Beijing train Pacific island police, become involved in cybersecurity, expand political ties, conduct sensitive marine mapping and gain greater access to natural resources on land and in the water.

As an enticement, Beijing offered millions of dollars in financial assistance, the prospect of a potentially lucrative China–Pacific islands free trade agreement and access to China's vast market of 1.4 billion people.

But the small island nations saw through Beijing's "disingenuous" offer, preferring instead to remain independent of Chinese influence in government and industries.

![Chinese military personnel in June simulate an invasion using amphibious landing vehicles, which Beijing vows to use one day against Taiwan. [Chinese Ministry of Defence]](/cnmi_pf/images/2022/09/21/37210-amphibious-585_329.jpg)