LIMA, Peru -- Peru suspended clinical trials of a COVID-19 vaccine made by Chinese drug giant Sinopharm after detecting neurological problems in at least one of its test volunteers.

The Peruvian National Institute of Health said Friday (December 11) that it had decided to interrupt the trial after a volunteer had difficulty moving his or her arms, according to local media.

"Several days ago we signalled, as we are required, to the regulatory authorities that one of our participants [in trials] presented neurological symptoms which could correspond to a condition called Guillain-Barre syndrome," said chief researcher German Malaga in comments to the press.

Guillain-Barre syndrome is a rare and non-contagious disorder that affects the movement of the arms and legs. Peru declared a temporary health emergency in five regions in June 2019 following multiple cases.

In the 1970s, a campaign to inoculate Americans against a supposedly devastating strain of swine flu ground to a halt after 450 of those vaccinated developed the syndrome, which can also cause paralysis.

Peru's clinical trials for the Sinopharm vaccine were due to conclude this week, after testing about 12,000 people.

Almost a million people have received Sinopharm's vaccine for emergency use, the company's chairman said in November, though he did not provide a specific figure.

Many of the firm's trials are taking place overseas, including in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, Egypt, Pakistan, Jordan, Peru and Argentina.

The company claims to be "leading the world in all aspects" of vaccine development, although it has not offered clinical evidence from its trials.

Many who have been inoculated in China are not formal participants in drug-makers' trials and are said to have done so voluntarily.

However, observers say in the race to be the first country to develop a proven vaccine for COVID-19, Beijing has been enticing -- or strong-arming -- its citizens to receive the shot.

Growing skepticism

The lack of transparency from Chinese health officials and vaccine makers has undermined trust worldwide in China's COVID-19 vaccine candidates.

It also undercuts the Chinese regime's attempts to repair its battered reputation with a last-ditch push for a vaccine after it plunged the world into catastrophe by initially suppressing news of the pandemic.

A poll conducted Sunday (December 13), for instance, found that 50% of respondents in Brazil said they would not take a vaccine made in China, against 47% who would.

China has four vaccines, including Sinopharm, in the final stages of development and is well advanced with mass human testing in a number of countries.

But unlike the case for vaccines being developed by Moderna, AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson, Chinese drug-makers have published little information about the safety or efficacy of their vaccines.

Chinese vaccine frontrunners Sinovac and Sinopharm had pre-orders for fewer than 500 million doses by mid-November, according to data from London consultancy Airfinity -- mostly from countries that have participated in trials.

Britain's AstraZeneca, meanwhile, has pre-orders for 2.4 billion doses, and Pfizer for about half a billion orders.

As orders and faith in Western vaccines increase, the Chinese regime -- adoping a tactic similar to Russian President Vladimir Putin's recent publicity push for his country's experimental vaccine Sputnik V -- is stepping in to offer its homegrown jabs to poorer countries.

But the largesse is not entirely altruistic, with Beijing hoping for a long-term diplomatic return.

"There is no doubt China is practising vaccine diplomacy in an effort to repair its tarnished image," Huang Yanzhong, a senior fellow for global health at the US Council on Foreign Relations, told AFP.

"It has also become a tool to increase China's global influence and iron out... geopolitical issues."

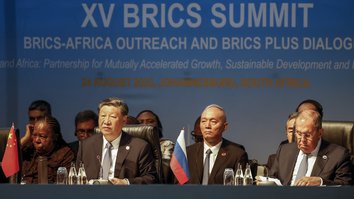

![A health worker prepares a volunteer to receive a COVID-19 vaccine produced by the Chinese firm Sinopharm during its trial in Lima, Peru, December 9. [ERNESTO BENAVIDES / AFP]](/cnmi_pf/images/2020/12/14/27443-000_8wt7jb__1_-585_329.jpg)